Introduction

Jukeboxes used to be the centre piece of a pub or bar. The locals would take turns playing their favourite tunes from the box and enjoy a variety of music. Can you imagine a bar, club or even your home without any music? The only way to get music of your choosing prior to the jukebox was by hiring a live band! The jukebox revolutionised music. It was a huge turning point in music and enabled artists a second revenue stream, selling vinyls. The jukebox has impacted modern society more than you can imagine and we're lucky here at Home Leisure Direct to stock some of the most infamous jukeboxes of all time. They are truly incredible pieces of art. The chapters are laid out below, you can skip to a section of your interest. Alternatively you can read the whole history of the jukebox and watch some of our great videos of them in action.

Chapter 1: The Development and Early Years of the Jukebox (1890s-1930s)

As is the case with many inventions, Louis Glass and William S. Arnold were not the only ones to conceive the idea of a coin-operated phonograph at that time in history. In the UK, Charles Adams-Randall requested a patent for his Automatic Pariophone in 1888, and Albert K. Keller in the USA claimed to have been working on the first coin-operated phonograph since 1887 and that his first model was, in fact, manufactured just a few months earlier than Glass and Arnold’s initial model that had been presented at the Palais Royal Saloon in San Francisco, California on November 23, 1889. However, Glass and Arnold’s nickel-in-the-slot phonograph was the first official and public example of a working coin-operated phonograph, so it retains the honour of being the first of its kind.

The success of Glass and Arnold’s model (they claimed their machines had earned over $4,000 in just the first year alone) lead to more people entering the business of manufacturing and planting coin-op phonographs in public places all over the USA. Albert K. Keller was the first to truly be successful at profiting from coin-op phonographs, but he was quickly followed and overtaken by other manufacturers, including the “Big Four”—AMI, Seeburg, Wurlitzer, and Rock-Ola.

This early time period in jukebox history saw several innovations to the “coin-op phonograph” design in rapid succession:

- Emile Berliner paved the way for the transition process from cylinder-based phonographs to disc record-based ones when he marketed for his gramophone in the 1890s.

- The John Gabel Manufacturing Company produced the first automatic multi-selection coin-op phonograph in 1906. This was known as the Automatic Entertainer, which had 24 songs for customers to choose from.

- The first electronic vacuum tube amplifier created in Bell Labs in 1916 allowed for the first commercial electric loudspeaker to be manufactured in 1924. This “electric amplification” of sound replaced phonographs’ earlier acoustic methods via listening tubes and horns.

- The first all-electric home phonograph was manufactured in 1924 by the Brunswick Balke Callender Company. A fully-electric phonograph with a true “loudspeaker” meant that an entire room of people could hear the music being played.

- Electronically recorded 78rpm records began replacing acoustic disc records around 1925-1926.

- In 1927, AMI created the first phonograph system that could play both sides of a record. This revolutionary development immediately doubled the number of songs available to customers.

- The coin-op phonograph design continued to be tinkered with and improved upon throughout that time period, particularly in the areas of the number of songs in the phonograph’s playlist and the process of streamlining and advancing the electronic mechanisms of the machine bit by bit.

It wasn’t until 1937 that the music-playing machines began to be called “jukeboxes.” The origin of the name is believed to be derived from the word “jook” (other spellings include “jouk,” “juke,” and “jute”), which was used as a slang term for dancing and acting wildly or disorderly. The word “jukebox” most likely originated in the Southern states of the USA where African slaves went to “juke joints” after working the fields for some fun and dancing.

One misconception still prevalent today is that jukeboxes were also known as “nickelodeons.” It appears that the confusion originated in the song “Music! Music! Music! (Put Another Nickel In)” by Stephen Weiss and Bernie Baum (1949). The lyrics describe putting another nickel in a “nickelodeon” for more music; however, there is no evidence prior to this song that coin-op phonographs were ever called nickelodeons. Instead, historical evidence points to the word solely being used for movie theaters that charged a nickel for admission.

Since coin-op phonographs were introduced, first in the USA and then in Europe, they grew in popularity, and their use became widespread. They were particularly great for individuals who wanted to listen to recordings of classical and orchestral works, which would otherwise have to be listened to live in person or on the radio. Also, black musicians considered the jukebox their best option for reaching the masses with their music, as the radio generally played only “white music” during that time period.

When the radio became an alternative source of “free” entertainment in the 1920s, record sales—and with them, coin-op phonograph sales—took a serious hit. On top of that, the Great Depression arrived in the 1930s, adding enough damage to sales to almost wipe out the record companies completely. However, the end of the 1930s saw a dramatic rise in sales for both records and jukeboxes; people had survived the financial crisis and wanted to “live” again. This rebound in sales quickly turned the jukebox into a fad that would make it a cultural icon for decades to come. The jukebox industry was about to enter its Golden Age.

Most iconic jukeboxes of the era:

- The nickel-in-the-slot phonograph (1889)—in article

- Gabel’s Automatic Entertainer (1906)—in article

- Link’s Autovox (1928)—top-end jukebox; ten turntables!

- Holcomb & Hoke’s Electramuse (1928)—well-known example of the style of the era; also one of the first fully-electric phonographs. Very popular

- Gabel’s Starlite (1936)—first jukebox to feature lighted columns

- AMI’s Top Flight (1936)—excellent example of the art deco style of that time period

Chapter 2: Rock ‘n’ Roll and the Golden Age of the Jukebox (1940s-1950s)

When the popularity of the jukebox started to rise again at the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1940s, manufacturers began using more elaborate designs that would catch customers’ eyes. Jukeboxes were no longer just wooden boxes; now they had metal castings, plastic parts, and even tubes of cellophane worked into their design. They mimicked the art deco style, they used bright and colourful lights, and they came in other shapes besides just a rectangular prism.

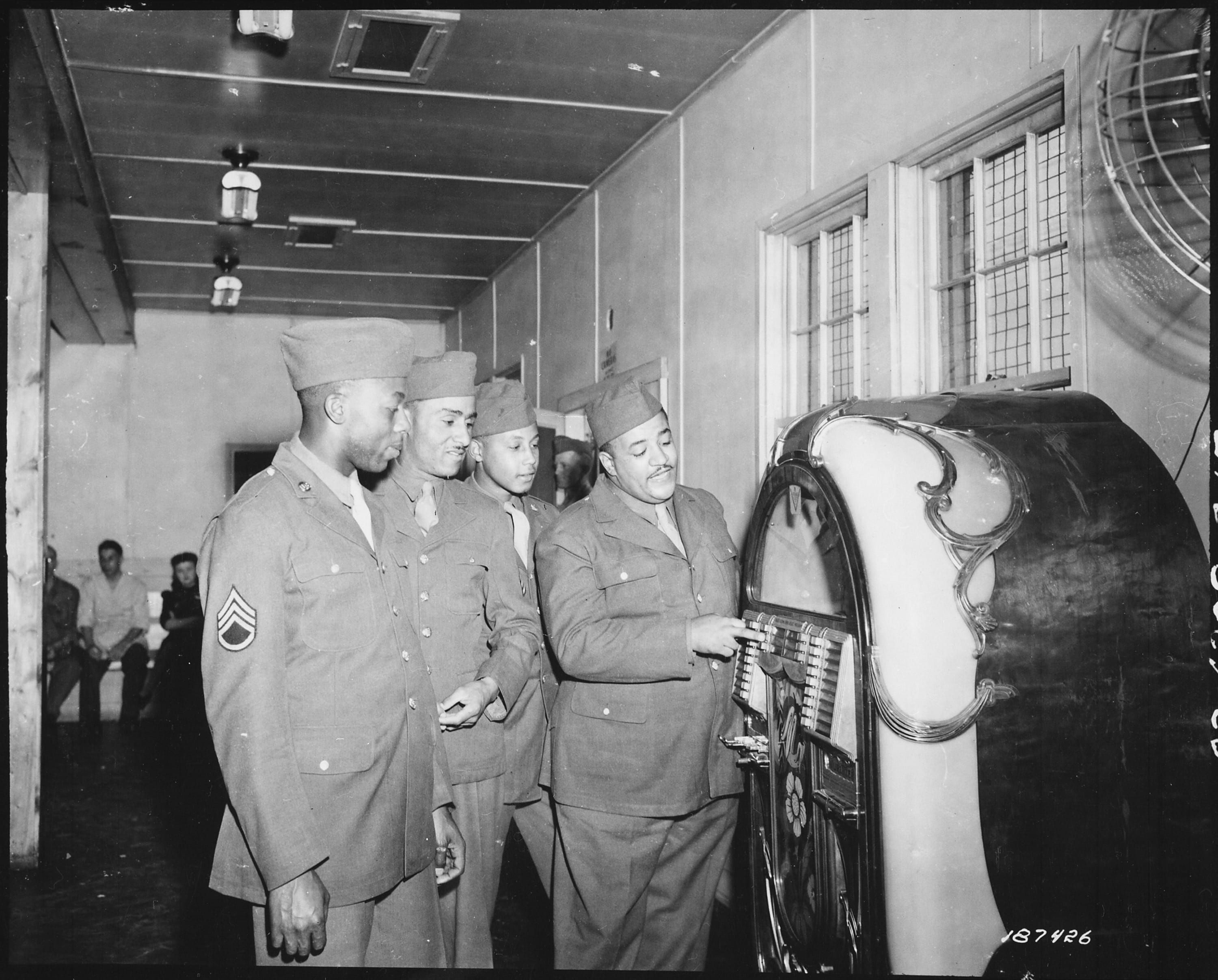

The production of jukeboxes was halted in the USA during World War 2 (from 1942-1946) in order to pour resources and labor into the war effort, but the jukebox industry came back in full-swing afterward. In fact, perhaps the most iconic jukebox of all time was released that very year by the Rudolph Wurlitzer Company—the 1015 model (aka, the Bubbler). The 1015 model had tubes of flowing bubbles that moved along the machine’s arched top. The design of this Wurlitzer model has been an inspiration in design for jukeboxes ever since.

Perhaps the rest of this time period would have seen the jukebox’s place in culture remain homogeneous throughout with the occasional leap forward in innovation and technology had it not been for one revolutionary change—rock ‘n’ roll.

The 1940s had plenty of jazz and swing music for dancing. Jukeboxes were competing well against the presence of the radio. Record sales were at an all-time high. Yet the new era of rock ‘n’ roll centralised the position of the jukebox in society, particularly for teenagers. Rock ‘n’ roll, unlike any music genre before it, belonged to the youth. It was the great divide between teens and their parents; the former were crazy for it, the latter thought it opened the door to all forms of degenerate and immoral behaviour in their children.

This had been the reputation of jazz music too, but the difference between the 1930s-1940s and the 1950s was a shift in audience and location. Pre-1950s jukeboxes were associated with unseemly places like bars and brothels—places for adults, not for kids. People went to these seedy places to drink, dance, and listen to the common man’s/black man’s music. Yes, jukeboxes were also located in many public places and used for more “high society” forms of music, but they were connected to places of indiscreet reputation nonetheless.

In the 1950s, however, teens were flocking to restaurants and diners to get their rock ‘n’ roll fix. Unlike the adults of that era, the youth of the 1950s didn’t need to go to bars to “let loose,” much to the annoyance of other customers in the diners and restaurants. In this way, rock ‘n’ roll formed teenage social life and culture, and it determined the most popular teen hangout spots—wherever the best jukebox was.

The greatest evidence for the jukebox’s shift in role and audience is in its design—it is undeniable that the jukebox’s appearance dramatically changed during the 1950s in order to imitate the style and look of the flashy cars of that time period. No more wooden boxes—chrome, brightly-coloured plastics, bubble tubes, steel castings, grills, and tailfins were the new clothes of the jukebox, and it wore them very well.

For this brief moment in history, the jukebox was no longer in league with the radio. It had become a fad, a mania, a craze, and its legacy in the pop culture of the 1950s was ensured. All of the important factors had lined up perfectly for its success: teens were buying rock ‘n’ roll records at an alarming rate, the 78rpm record had been replaced by the smaller and more cost-effective 45rpm record, and new innovations in jukebox technology made the machines all the more accessible and fun for customers. Rock ‘n’ roll elevated the jukebox’s status in society, and in return, the jukebox supported the teenagers’ hunger for more rock ‘n’ roll. It is no wonder that business boomed for the jukebox industry during this time period.

Wurlitzer’s name was practically synonymous with the jukebox during the Golden Age. Not only were its machines top quality, but it had employed Paul Fuller, arguably the greatest jukebox designer of all time. Wurlitzer was a company with a long history, tracing its business in musical items as far back as the 17th century in Saxony. Rudolph Wurlitzer moved to the USA in 1853 and made a business out of coin-op player pianos and large theatre organs. It wasn’t until 1933 that the company began manufacturing coin-op phonographs in North Tonawanda, New York, but once Wurlitzer got into the business, it dominated until the beginning of the 1950s. Its 1015 model alone sold more than 56,000 units in 1946, and that was under the slogan, “Wurlitzer is Jukebox,” which was very close to the truth up until that point.

.jpg)

Wurlitzer was dethroned in the 1950s by the Seeburg Corporation due to its many innovations in jukebox technology. J.P. Seeburg founded the company in 1907 in Chicago, Illinois as a manufacturer of orchestrions and automatic pianos. However, in 1927, the business switched over to manufacturing coin-op phonographs. Seeburg never caught up to the success of Wurlitzer until it created the Select-O-Matic in 1949. At that time, every jukebox, including Wurlitzer’s, could only play between 20-40 songs, but the Select-O-Matic (aka, M100A model) was able to play 100 songs! This was due to the innovative rail system used in Seeburg’s machine that stacked the records horizontally instead of vertically. That same year, Seeburg introduced the Wall-O-Matic (aka, the 3W1 Wallbox) which would become incredibly popular in every diner and restaurant for the next 20 years. In 1950, Seeburg continued to innovate by being the first manufacturer to use 45rpm records instead of 78rpm records in its jukebox. This switch from 78rpm’s to 45rpm’s was in large part due to the recording ban of 1948. Subsequently, all jukeboxes made prior to 1950 became obsolete in the consumer’s mind, despite the fact that many models were still in perfect, working condition.

Seeburg’s innovations changed the face of the jukebox industry. 45rpm records were used in jukeboxes for the next three decades. Later that same decade, jukeboxes were boasting twice the number of songs Seeburg’s M100A model had. Most, if not all, diners and restaurants had Wall-O-Matic remote control units at every table, bar, and counter.

There were two more jukebox manufacturers during this time period that also sold very well. They are the final members of the “Big Four” in the jukebox industry. AMI (Automatic Musical Instruments, Inc.) began producing jukeboxes in 1927 in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Rock-Ola began in 1935 in Chicago, Illinois. Both companies were successful, especially during the 1940s and 1950s, but they never matched the success of Wurlitzer or Seeburg. AMI sought to rework and improve upon the Seeburg innovations; by 1956, its G200 model could play 200 different songs by incorporating a rotating magazine. Rock-Ola was known for their Luxury Light-Up series in the early 1940s. They were the first to produce a jukebox after the war (their 1422 model in 1946), and they also specialised in miniature jukeboxes, counter-top jukeboxes, and wallboxes, which were obviously influenced by Seeburg’s design.

Rock-Ola’s Luxury Light Up Below:

Rock-Ola's 1422 below:

Rock ‘n’ roll was here to stay, but the end of the 1950s was the end of the jukebox’s heyday. Never again was the jukebox to see a surge in popularity like it did during the 40s and 50s. As is the case with any fad, people (especially teenagers) are quickly distracted by the latest novelty or next “big thing.” Such is the case for the jukebox, which fell victim to being unable to keep up with the times.

Most iconic jukeboxes of the era:

- Wurlitzer’s 1015 model (the Bubbler)—in article

- Seeburg’s M100A (Select-O-Matic)—in article

- Seeburg’s 3W1 Wallbox (Wall-O-Matic)—in article

- Seeburg’s Trashcan series (1946-1948)—interesting design and sold more units than the Bubbler.

- Rock-Ola’s 1422—in article

- Rock-Ola’s Luxury Lightup series—in article

Chapter 3: New Competition and Nostalgic Adoration (1960s-1990s)

The jukebox continued to remain popular throughout the 1960s but never to the degree experienced in the previous two decades. Rock ‘n’ roll was ten years old already, and other media outlets, such as the radio and TV, were catching up to the trends set by the new generation’s passion for rock music. Pop radio stations and TV shows that showcased the talents of contemporary musicians—regardless of skin colour—began to dip into the monopolistic hold that the jukebox had once enjoyed among the teens.

Another detrimental blow to the jukebox’s popularity was the shift in teenager life away from hanging out at the diners and restaurants. The 1960s were the hippie era; it was also the beginning of Beatlemania and the mainstream success of rock concerts. Live music had recaptured the hearts of the youth. Teens suddenly had new places to go for both their music and their social lives.

The 1970s onward only made the jukebox’s predicament worse. In addition to rock concerts, teens had nightclubs and discotheques that suddenly catered to them and their tastes in music. These new places for socialising and dancing provided either live music or DJs who had a whole new arsenal of technology and methods to get the crowds of club goers pumped and partying.

It appeared that the jukebox’s relevance was finally doomed when the disc record’s status as the audio playback medium of choice was dethroned after more than half a century. The 1980s saw the audio cassette as the first popular replacement. The audio cassette had been around for a while already, but the portable cassette player came out in the 1980s, and that changed everything. People could suddenly have a privatised music experience wherever they went. In the 1990s, the cassette was replaced by the CD (compact disc), which simultaneously continued the trend of providing portable listening experiences and improved upon the medium’s format.

With the rapid rise of alternative audio media and technology during this time period, what place did the jukebox have in society any longer? Some critics have argued that by the 1990s, the jukebox had become an obsolete relic of the past, whose glory days ended shortly after the era of rock ‘n’ roll. While it is true that jukebox sales had dramatically declined since the 1950s, the jukebox was still around and still appreciated in the 1990s.

In the mid-1970s, the number of jukeboxes on the market was at an all-time low of around 175,000 units. That number remained steady all through the 1980s and put a lot of jukebox manufacturers out of business, including the American-based operations of Wurlitzer in 1973 and Seeburg in 1979. However, thanks to the CD industry and avid jukebox collectors, the number of jukeboxes being sold at the beginning of the 90s was bumped back up a bit. The number of jukeboxes sold each year has remained around 250,000 units ever since.

Despite being unable to compete with the newer and better forms of media that took over during the 1960s-1990s, the jukebox industry stayed alive for two reasons: the nostalgic value of the jukebox as an icon of pop culture and the interactive nature of the jukebox in a group setting.

It is interesting to note that the jukebox’s design hasn’t changed that much since its heyday. Yes, the excessive chrome and car-like features had been discontinued, but the manufacturers’ choice to preserve the look of the jukebox of the 1940s and 1950s says a lot about consumers’ expectations. The jukebox was an icon, and that meant future models had to present themselves as an extension of that legacy. In fact, both Wurlitzer and Rock-Ola churned out replicas and tributes to the bygone era of the jukebox in order to capitalise on the nostalgic feelings of adults who had been teens during the 1940s and 1950s. In 1973, Wurlitzer produced their 1050 model, named “The Nostalgia.” The company went even further by re-releasing the 1015 model design in 1987 and calling it “the OMT model,” which was an acronym for “the One More Time model.” Rock-Ola used both Wurlitzer designs in their own releases—the Rock-Ola Nostalgia 1000 (in 1987) and the Rock-Ola Bubbler Nostalgic (in around 2001). Both AMI and Seeburg released similar “retro jukeboxes” as well: AMI’s Laserstar Nostalgia and Seeburg’s Seeburg Classic models (SCCD series).

The OMT Model:

These nostalgic models were greatly appreciated by jukebox lovers and collectors, but the Big Four’s efforts weren’t enough to bring jukeboxes to the forefront of society’s attention again. It was clear that the jukebox’s time had passed, and now, it was expected to keep up appearances in accordance with that past.

But the jukebox very much remains an experience of the present as well, due to its unique position in the audio entertainment industry. Like portable music players, the jukebox is intended to be interacted with on a personal level—the customer inserts money in order to pick song selections. However, unlike the portable music players of the 1980s and 1990s, the jukebox is intended to be heard by an entire room full of people, not just the individual who picks the song. The radio does something similar—it plays popular music in a social setting for everyone to enjoy; however, there is no song-choice interaction at all.

Rock-Ola Bubbler Nostalgic:

These comparisons make it clear that the jukebox fulfills a specific need in society and culture, and it does so while stimulating multiple human senses simultaneously—sound, sight, and touch. It is not that surprising, therefore, that the jukebox continued to be present in bars, at special events, and in the homes of collectors and enthusiasts at a time in history when the audio entertainment industry seemed to have moved on from the days of the jukebox. It remained in play against the new competition because of its nostalgic appeal and the human desire to choose songs for others to listen to.

Most iconic jukeboxes of the era:

- AMI’s Continental series (1961/2)—very “sci-fi” and eye-catching design that was popular at the time

- Wurlitzer’s 1050 – the Nostalgia (1973)—in article

- Cameca’s Scopitone (1960s)—combining songs with video, a precursor to the music video

- Wurlitzer’s C-110 Cassette Jukebox (1972)—a failed attempt at using audio cassettes instead of disc records in a jukebox

Chapter 4: Trial by Fire Has Proven the Jukebox’s Value (2000s+)

In the 2000s, a major change took place in the way people listen to music—the internet and the .mp3 audio format made music accessible like never before. MP3 players replaced CD players, digital music libraries online replaced the need for physical collections of music, and smart devices, such as smart phones and tablets, were capable of playing music out loud like miniaturised versions of the jukebox.

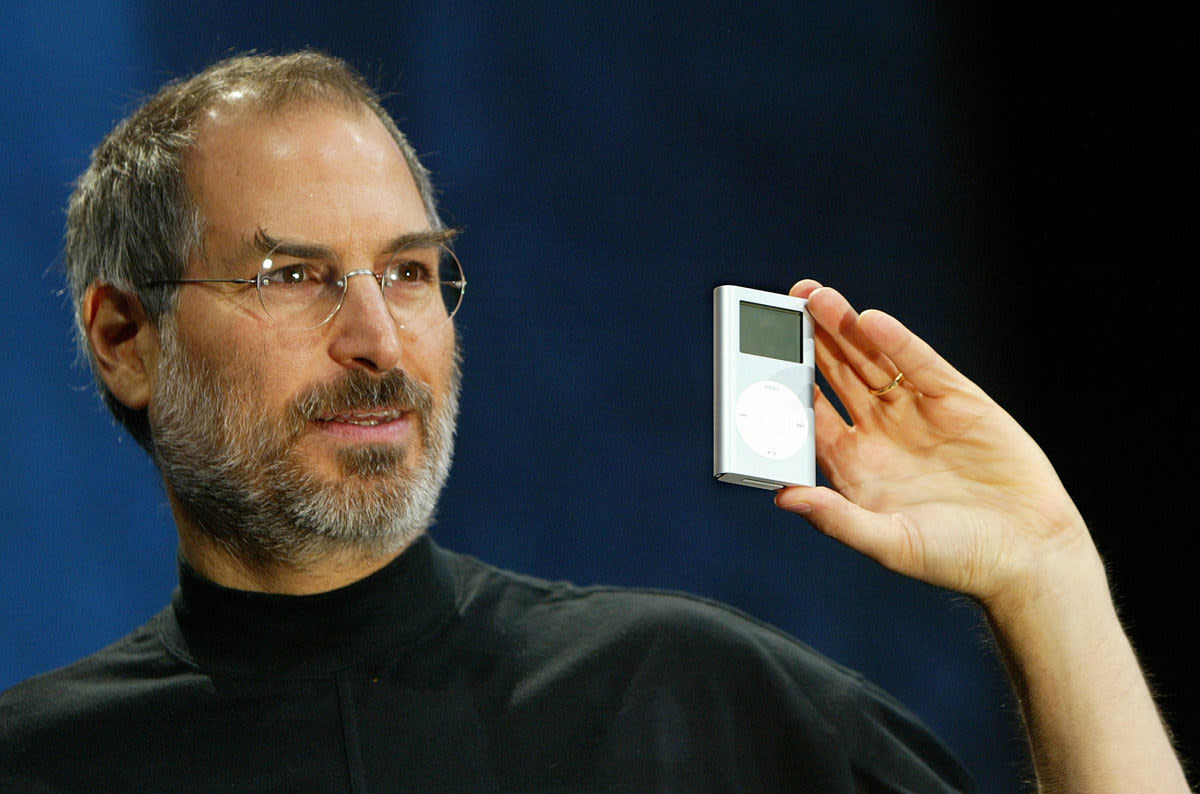

Steve Jobs Revolutionised Music With The iPod

All of these new developments appear at first to be major threats to the jukebox’s existence, yet the jukebox’s history thus far has proven that there will always be a need for its presence. These latest advancements in technology are not replacing the jukebox; rather, they’re being embraced by it. Since the beginning of the 21st century, jukebox models have been incorporating the ability to dock MP3 players in order to access their music libraries. Jukeboxes come with interactive touchscreens that display far more information than just the song title and band name, and more recent models, such as TouchTunes’ Virtuo (released in 2012), access online music libraries and can be interacted with via an app on a customer’s smart device.

The jukebox is far from being forgotten by the collective consciousness of society. As an example, many online music playlists and databases are listed as virtual jukeboxes or E-jukeboxes. Most recently in the 2010s, a new surge of interest in old-fashioned jukeboxes has occurred as well, thanks to the retro-inspired and nostalgically-inclined indie and hipster movement. There have been serious collectors of jukeboxes since the 1980s, but never before has there been such an extensive community as in the internet age that is built around the collecting and repairing of old jukebox machines.

The selling and buying of old jukeboxes, replacement parts, and re-manufactured 45rpm records have become multimillion dollar secondary markets, and community websites and online groups continue to grow in numbers. Two examples are the “American Historic Juke Box Society” (http://www.ahjbs-jukeboxsociety.com/) and “TomsZone” (http://www.tomszone.com), both of which cater to jukebox collectors by providing exhaustive details and resources about the jukebox and the communities surrounding it.

Of the Big Four in the jukebox industry, only Rock-Ola and AMI are still around. Wurlitzer’s Germany-based operations were taken over by the Gibson Guitar Corporation, which discontinued jukebox manufacturing in 2013. However, Gibson still provides replacement parts for Wurlitzer machines. AMI was merged with ROWE AC Services in the 1960s and was thereafter known as ROWE/AMI until 2007 when it merged with Merit Entertainment, the producer behind TouchTunes, and renamed the AMI Entertainment Network. In 2009, it acquired the commercial jukebox assets of Rock-Ola.

Rock-Ola almost went out of business in the 1970s and 1980s, but in 1993, it was bought by Antique Apparatus Co., which wisely chose to keep the Rock-Ola name alive. Today, Rock-Ola continues to be successful in selling jukeboxes and related products, especially its Nostalgic series. The company provides jukeboxes with a retro look combined with the latest technological advancements in the industry. Rock-Ola remains one of the top jukebox manufacturers in the world today.

Smart devices and “smart jukeboxes” are the future for the industry, but there is still a place for the older, more traditional machines in modern times. It is uncertain how long the latest generation’s interest in the retro appeal of the jukebox will last, but there will always be collectors on the hunt, and there will always be nostalgic value in play. The jukebox holds a special and unique position in society. It fills a need that has existed since the creation of music, and it will continue to meet that need no matter what form or design it comes in.

Most iconic jukeboxes of the era:

- Rock-Ola’s Bubbler Nostalgic (2001)—in article

- TouchTunes’ Virtuo (2012)—in article

- Secret DJ (2012)—one of many “jukebox apps” that provides music libraries for thousands of locations with jukeboxes in order to build customer loyalty and virtual jukebox interaction and community.

Chapter 5: Jukeboxes in Action

Sound Leisure 1015

In this video, Home Leisure Direct showcases the incredible design of Sound Leisure’s 1015 model, manufactured in the UK and based on the original 1946 design of Wurlitzer’s Bubbler. The jukebox in the video is Sound Leisure’s slimline model, which is 54 cm deep and has a hand-built blonde oak frame as well as the optional ipod/iphone dock. It holds 80 CDs that can be chosen from either the buttons on the front panel or via remote control. In this video, the optional diamond light pack is demonstrated. It features ten different lighting patterns with the last two directly reacting to the music being played.

Sound Leisure Rocket 88

The Rocket 88 features plenty of glass and chrome as well as a name that pays tribute to the very first rock ‘n’ roll song—Rocket 88 by Jackie Brenston and the Delta Cats in 1951. Though it is reminiscent of the Rock-Ola style of the 50’s, this is actually a 21st century jukebox by Sound Leisure and manufactured in the UK. It holds up to 80 CDs and includes an optional ipod/iphone dock. This video from Home Leisure Direct shows its ability to seamlessly transition from ipod to CD.

Wurlitzer 2300S

This jukebox was made in 1959 by Wurlitzer and has since been restored and preserved beautifully. It is the top of the range of 6 models that Wurlitzer made in this particular series. It is the only 2300 model that can play 200 selections from 45rpm records. It is a very collectible jukebox because it was Wurlitzer’s first stereo jukebox, and it magnificently represents the chrome and lighting designs of that time period.

Wurlitzer 1900 Centennial

The Centennial model is a classic design preserved from the Silver Age of jukeboxes. It has plenty of chrome and beautiful lighting. What makes it so collectible is how perfectly it represents the jukeboxes of that era as well as its role as a commemorative piece in celebration of Wurlitzer’s hundredth year back in 1956. It holds 52 45rpm records for a total of 104 song selections.

Rock-Ola 1468 Tempo 1

This 1959 jukebox has been restored and preserved in perfect condition. The design closely resembles the iconic look of cars of the 1950s. Rock-Ola manufactured this model in 1959. It plays 60 45rpm records for a total of 120 song selections. Besides the chrome fins and Cadillac-like V-shape on the speaker panel, what makes this jukebox unique and collectible are the three buttons at the top which group the song selection into three categories or styles to choose from. This video from Home Leisure Direct shows how it works.